Has your grown up life had as much music making, art making, and dancing as you'd like?

A missive in which my father thinks being a good singer is the only reason to sing and I deprogram the idea that artistic play is only for kids.

What did you learn from your parents about play and art? Living here at this time of my life, with a bit more objective awareness and far more conviction than I’ve ever had, has been almost exhilarating (and sad) in witnessing exactly where some of my programming comes from as opposed to a vague feeling that it exists and has been a block.

My father fully believes that the only things worth doing are the kinds of things one can be paid for or that provide things that support our survival. Working, of course, for pay, is at the top of the list. But barring that: hauling in trees for our wood burners, planting and tending a garden, pushing snow/mowing the grass, sealing the seams of the log house, building things like shelves and a bathroom.

The only true pleasures he occasionally indulges in (while he complains he doesn’t get to do them more) are hunting and fishing, which could be argued originate from a position of providing food, however, I’ve learned he catches more fish than he brings home and, don’t tell his brother, but he’s said more than once now that he’s not that bothered if kills a deer, but really enjoys sitting in the treestand watching them and other wildlife at 6 a.m. in the cold (he must really enjoy it).

But he does those things under the guise of being productive. He does not take the boat out to sit in it without his rod and he does not sit in the treestand in the off-season (which is 49 weeks of the year) just to see what he might see because that would be a precious waste of time, that limited resource most are so worried about.

Don’t tell him I said this, because he already goes on and on about how much work he does and how he never gets to rest, but it’s true he really doesn’t know how to stop. Neither did his dad, who I found, at 70-something and near immobile outside in the driveway on a warming spring day chipping away at the thick layer of Minnesota ice surrounding a three-foot square patch of driveway he’d managed to uncover over the winter months, painfully aware that it would all melt well before he ever managed to clear the ice entirely from the driveway.

So it didn’t surprise me that when I made some crack about fantasizing about being on The Voice (which he watches religiously) and all four chairs turning for me and then four famous fucking musicians get to FIGHT over ME! It’s not so much that I actually want to be on The Voice or even want to be a great singer, it’s just that I’d take oh so much pleasure in being valued by people already established in their careers.

Oh, you all want little old me? Who’dathunkit? Then they get to tell me how amazingly fabulous I am and how they long for me to be on their team. Because, obviously we all want to be fabulous to someone and especially to those who have some idea of what fabulous is in our given practices.

But Dad says something like: “You’re not good enough for The Voice. It’s a shame, too, we both like to sing so much.” As if not being good enough for public consumption and winning competitions (read: earning money) and finding joy for joy’s sake in singing are mutually exclusive. We can only engage in and find joy in belting “Unchained Melody” out to our little heart’s content if we are in some form being compensated for it?

How is that the point of anything at all?

He also firmly believes that 100% innate talent is everything and that practice and skill-building are more or less inconsequential? Here, folks, he is making a strong example of a “fixed mindset.”

And by some miracle, I’ve learned, despite this dude being my father, a “growth mindset,” in which I may not ever be a fabulous singer, but just a browse around the internet tells me there are vocal warm-ups to keep my vocal cords warmed and healthy. There are skills I can learn to improve my technique.

And, frankly, there’s a whole catalog of music that proves one doesn’t always have to be a fantastic vocalist to have some success at singing. But shrug, I’m happy wailing to “What’s Up?” alone in my bedroom. No audience or judges needed, but you’re welcome to join me in a sing-along.

In Freedom Manifesto, Tom Hodgkinson points out that music in the Middle Ages wasn’t centralized and commodified as it is now, oh sure there were troubadours and artists and playhouses that hoped for your hard-earned shillings, but music, art, poetry, and playacting also happened in the home and in communities for little to nothing often carried out by amateurs. There were no gatekeepers or capitalist barricades insisting that the only quality music (and that’s arguable) is offered to the public by the music industry at a price (not that those artists don’t deserve to be paid for their work).

People just did as they enjoyed, often together.

Back when I lived in Bath, my local, The Royal Oak hosted an Irish Music Night, which is a lingering example of inclusive and joy-filled music-making. One musician starts a traditional Irish song and those who know it jump in. Those who don’t play, have feet: they can dance.

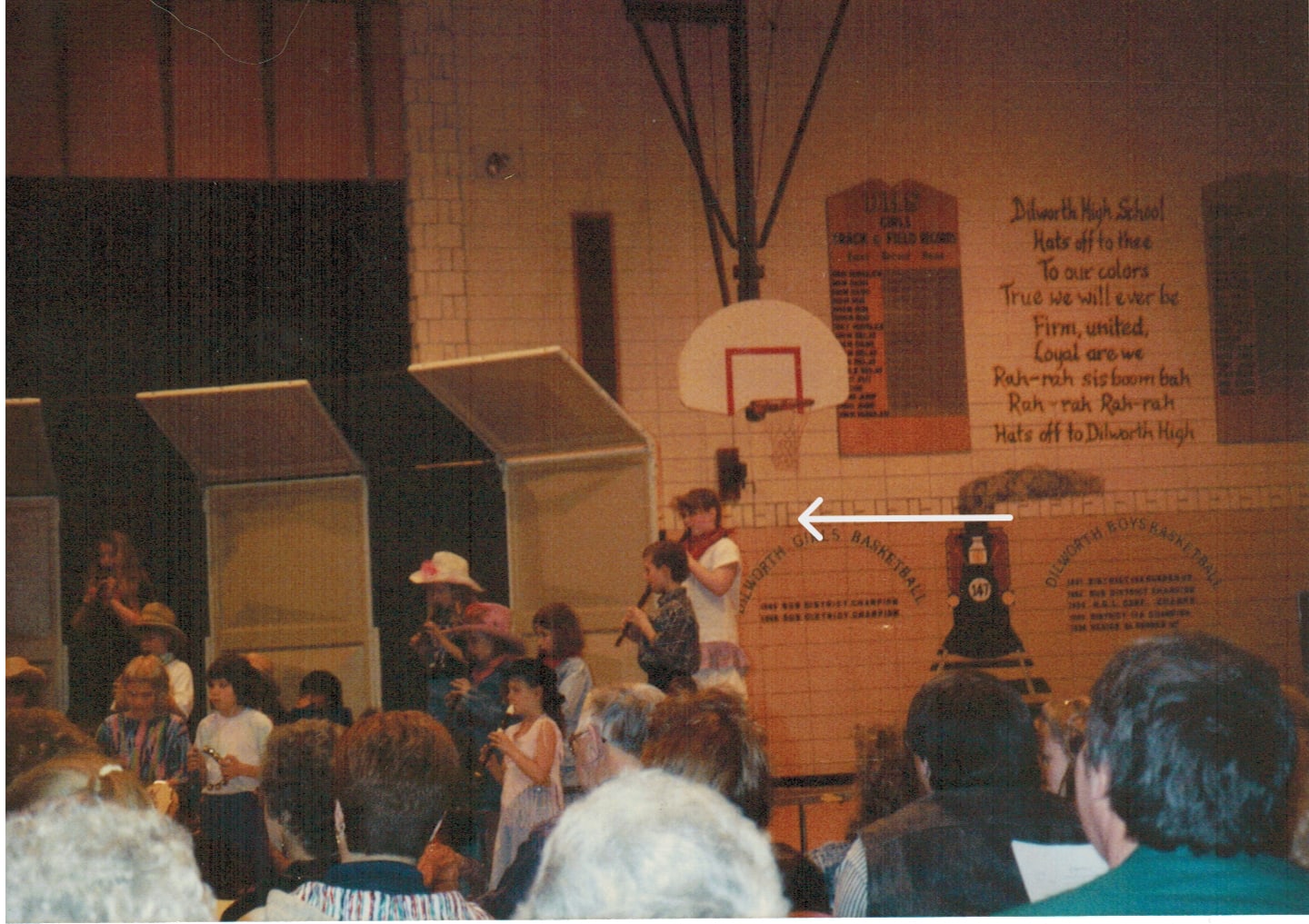

I started learning the trumpet when I was 10 or 11 years old. I absolutely loved to sing. I performed in plays and skits. All of which were part of the school system. I was also part of a dance company that wasn’t affiliated with the school. None of it, not even the primary school performances, had the vibe of a community coming together to amuse themselves or merry-making for its own sake, not like an Irish Music Night. However amateur, it was arranged, practiced, directed, and presented to an audience of spectators (our parents).

It didn’t take me long to see that art, music, dancing (outside of wedding dances) were things kids did and then kids grew up. Though, of course, there were examples all around me of grown-ups making things (I mean the TV was always on in our house, what better example of grown-ups playing than acting?!), I got the impression that I was precluded, and subsequently that I wasn’t creative enough or artistic enough (i.e., not good enough for The Voice). And this is probably why I loathe to become a grown-up.

Grown-ups aren’t encouraged to play and be playful. To dink around. To be weird and messy and silly (unless they have or make loads of money doing so), which is how artists learn and develop and make innovative things. That’s where creativity thrives, not sitting at desks in an open-floor office plan checking one’s email 300 times a day or being overloaded with assigned projects and fires to put out, which is common in our contemporary working world, or even in the regimented practicing of scales or carefully drilled dance numbers in which I took part as a child.

What’s it they say about writing? You must learn the rules of grammar first and then you can creatively break them? Well, I’ve seen some really bloody lovely lines come from non-native English speakers precisely because they didn’t quite understand the rules of grammar.

But, as such, I learned that play had to happen in private where it wouldn’t be judged or silenced or cajoled into being made better. In fact, I hardly learned to play at all without someone guiding me.

During my MFA at SAIC, I was introduced to so many art disciplines and fortunately for me my soul is drawn to making things and exploring things and learning things and whatever setbacks I’ve faced and whatever programming I’ve internalized, very slowly I have allowed myself to gently press up against my boundaries and develop new skills and play with new tools and ways of making.

I recently forgot that for some months, but thank the universe for my soul, because the other night I just felt like I needed to do something visual. The things I was doing last spring didn’t feel like the things I needed, so I pulled up the courses I purchased on Domestika to find something new and landed on watercolor.

Aaaaaand I found myself crying as the instructor introduced us to her practice. A clear sign this is what I needed.

Take your brushes out for a dance, she says, and so I did, just making silly marks to explore what the different brush shapes and sizes did and I was reminded of that feeling the brush makes in my hand that just feels right somehow. And whether or not I ever paint anything that’s worth any money or is even admired by any member of the public, is beyond the point, none of that matters, it’s the joy in the doing that truly matters.

Because it is true, time is a precious, limited resource, and each moment we live in joy, play, love, none of which are inherently related to compensation or even admiration, is what gives being alive value.

I think deep down Dad knows this, we all know this, it’s part of our DNA, our soul’s DNA, if you will. Because to some degree, I think we all yearn for it. And maybe your things aren’t painting and singing and writing but playing a game of football (the American kind or the rest of the world kind) in a park or bird watching or building things or cooking things. I mean whatever it is you’re drawn to doing with or without the money, is your deep knowing and believing that the doing is where the joy is.

And though he complains about all the stuff he has to do, deep down he must enjoy it, all those productive things he does, for he in fact chose this house with its 70 acres of trees, he dug his first garden, he has a garage full of tools, he takes pride in his tractor and his planer. And if he didn’t find joy in it all he would have bought a much smaller house on much less land and hired someone to take care of it for him while he fiddled with the bass he once learned to play on his own time in the practice rooms at school.

The only shame is that he doesn’t allow himself to do a lot more singing while he’s out there pulling in trees and tilling the garden.

Are you out playing today?

Sincerely,

P.S. I do know that I was privileged to have music and art options available in school. Many countries don’t generally and in the U.S. those programs are constantly under threat by legislation that considers them unnecessary and a waste of public spending for exactly the reasons my father thinks it’s a shame we’re not good enough singers to be on The Voice and therefore shouldn’t bother: there’s little chance of capitalistic gain if we teach everyone an instrument. But, in case you didn’t know, studies overwhelmingly show that kids who engage in music and art do better in math and therefore are valuable to capitalism.

So, you know, tell your legislatures.